I am including a video reading of this chapter. Take a listen!

Demetrius follows the woman through the front doorway. His first step onto the wide wooden floorboards of the dim front hall produces a loud croak. The girl, Samantha, imitates the sound perfectly as she pushes in beside him.

The woman shuts the heavy door and strides ahead past double doors on each side, tightly closed, their ornate trim scarred and peeling. The girl dashes down a hall beside a stately staircase that rises on his right. A gallery of child’s drawings crowds the wall to his left. As he follows the woman and girl down the hall, he admires the pictures, full of long-haired girls sitting on weeping houses, flying on broomsticks, and brandishing peculiar weapons.

Reaching a threshold, Demetrius halts and stands gazing at a kitchen like none he’s ever seen—an enormous room which at first seems a jumble of color. Blinking a few times, he notes plants of all sizes jostling each other along every wall. More plants crowd an oversized table, and bristle atop cabinets and counters—fishtail palms, pussy ears, a dragon tree, dozens more—a horticulturist’s jamboree. An amazing bird-of-paradise plant stands under a window in an ornately glazed urn. More plants hang from ceiling hooks; others sit on the window ledges, all in colorful ceramic pots.

Multi-colored ribbons flutter from the kitchen cabinets. Brightly colored animals, birds, and human figures of ceramic, wood, and tin adorn the walls, window sills, and every other surface not occupied by a plant.

At the far end of the room hang two large cloths tie-dyed in bursts of red, yellow, and orange. A similar tie-dyed cloth billows across the middle of the ceiling, like part of a theater set.

He feels as if he’s landed inside the painting of a chaotically colorful Haitian market that hung in the living room of his family’s old duplex. He takes a step forward, as if pulled back to that old room in their narrow house, blocks from what is now Liberated Zone, across from the Lilydale Street Krew’s alley hangout, where Officer Larsen was…

Stop! he commands his brain. No triggering allowed. You are a normal person on a Saturday—Sunday?—afternoon in November 2006, and you are asking to rent a room in this interesting house with its colorful, plant-filled kitchen.

He nods to himself. But the plant leaves rustle; ribbons shiver; the tie-dyed hanging cloths ripple gently. Demetrius feels queasy. To steady himself, he takes a couple more steps into the room. A glance out the window shows wind-tossed trees. The kitchen is not magically animated, he decides; it’s just the autumn breeze blowing in through decaying window sashes. “Wow,” he gulps, “what a fantastic room!”

“It’s our kitchen,” Samantha explains, “and our living room and office and playroom and…”

Marlie puts a hand on her granddaughter’s shoulder. “Yes, we spend much of our time here.”

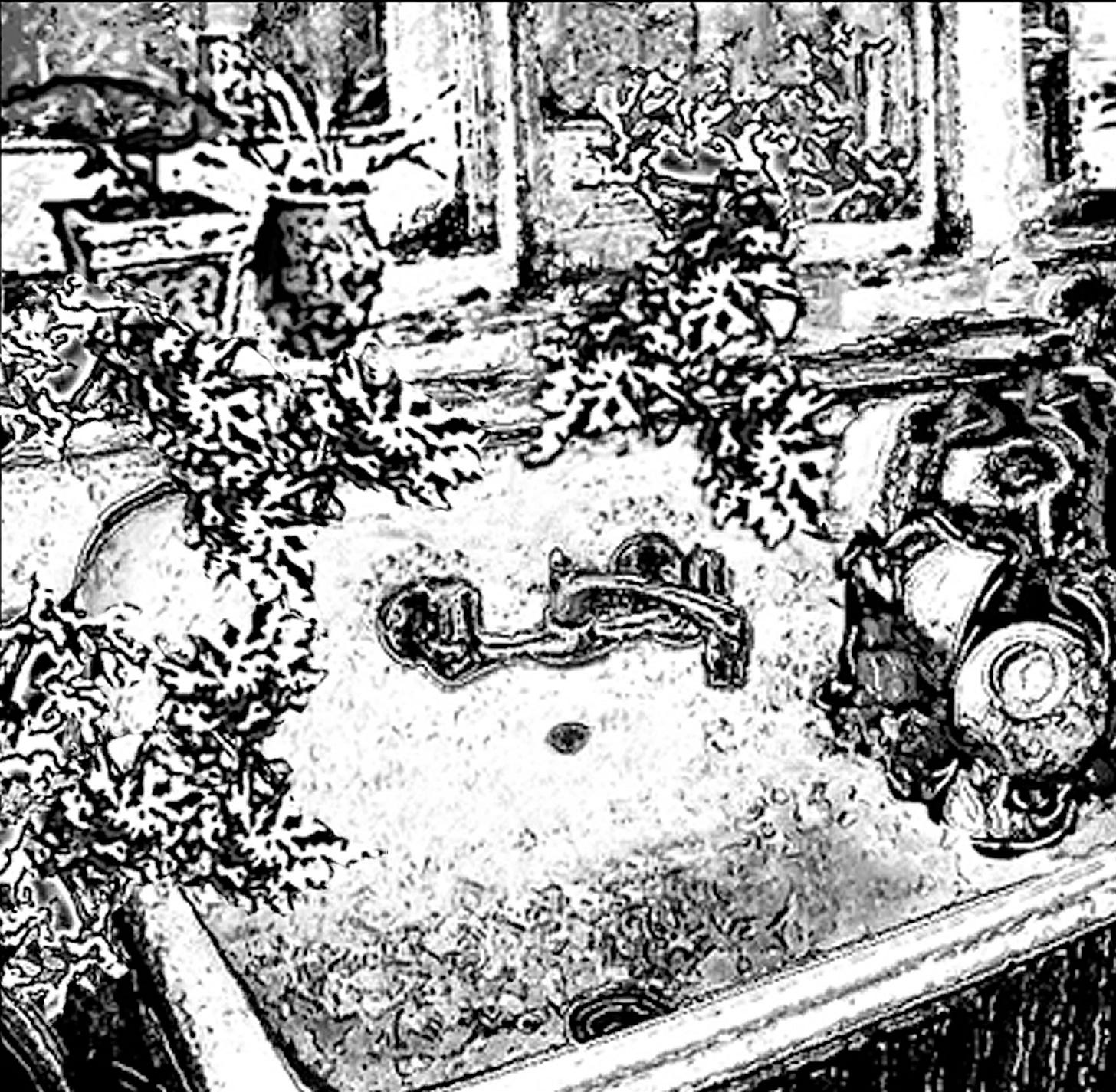

Unable to think of anything to say, Demetrius continues looking around, his gaze lighting on a white porcelain sink with rounded shoulders, a mottled cast-iron radiator coiled under it like a fat snake. Beside the sink stands its cousin, a hunched old refrigerator with a long chrome handle. Further along is an oversized, unsafe-looking stove straight out of the nineteenth century, with bulky knobs and clunky burners resembling black widow spiders. Daintily painted curlicues decorate its chipped enamel surfaces.

Across from the kitchen appliances, a bright blue door lies across two squat filing cabinets, forming a desk. Upon it sits a fuchsia-colored laptop, along with several succulents and spider plants. Next to the desk is a slender orange bookcase with a small red television on it, crowned with a bushy African violet. Several child-sized chairs face the TV. Demetrius’s imagination conjures a dark-faced, red-haired nursery teacher in a purple flowered hat and an orange dress, teaching a class of invisible tots.

He gives his head a shake, feeling he must say something. But after his flood of talk on the porch, now that he’s surrounded by things he could safely comment on, he feels only able to stare.

Along the kitchen’s right-hand wall sits a short, plump couch, covered in yet another tie-dyed sheet, under a window with a sill full of herbs and a sprouted avocado. Samantha flops onto the couch and begins paging through a large picture book.

He turns to his host, willing her to speak; but she seems as tongue-tied as he is. “Wow,” he repeats. “This is paradise for anyone into plants!”

Marlie nods, but wonders if he is sincere. She loves her kitchen, but worries a normal person might find it outlandish. She grimaces, feeling irritated at this worry. Then, fearing the visitor will think she’s frowning at him, she turns her head and notices the full jar of rice. Further annoyed because she has neglected to start their dinner, she turns to the man. “I trust you can cook.”

His eyebrows shoot up for a second, but he exclaims affably, “Sure! I was chief cook when I lived with my grandmother. I love cooking!” He takes a couple of steps toward the stove, as if drawn to it.

“I hate cooking.” Marlie has not intended to say this, at least, not so vehemently. But it’s true. If not for needing to give Samantha a balanced diet, Marlie would eat corn chips and hummus or bagels and cheese for every meal—plus random raw fruits and vegetables. Along with coffee and chocolate, of course.

Samantha raises her eyes from her book. “I love cooking, too.”

“Wonderful! We’ll make a super team.” Demetrius blurts this out, then meets the woman’s eyes in embarrassment. “Sorry,” he fumbles, “I’m getting ahead of myself.”

“Well, I guess I did, too,” she replies. “Asking you about cooking when I haven’t even introduced myself. I’m Marlena Mendíval. North Americans call me Marlie.” She holds out her hand.

“Pleased to meet you,” he says.

She clasps his hand, then pulls away. “Your hand is so cold!” She gives an embarrassed laugh. “Sorry to be rude. I should be used to cold hands, since I work outdoors.”

“Really? Where do you work?”

She cocks her head north. “University of Maryland, College Park.”

“For real?” he exclaims. “That’s where I studied!”

He almost claps a hand over his mouth at having revealed this major fact about himself. At the last instant, he redirects the impulse into scratching his chin.

The woman, Marlie, doesn’t appear to notice. “That’s a coincidence,” she says lightly. “I’m a campus groundskeeper. I mean, a ‘landscape technician.’” She makes a wry face. “Instead of good wages, they give us fancy job titles.” With a smile she adds, “Sorry if my view of your alma mater is somewhat jaundiced.”

Demetrius chuckles. “No worries, I’m hardly a flag-waving alum. I encountered plenty of racism there as a student, though also a lot of great people.” He notes her sympathetic nod.

He angles himself towards the table, hinting at an invitation to sit. But the woman seems oblivious. “The university is just as exploiting as other big employers,” she remarks.

The portion of his mind not focused on his own desperation realizes with embarrassment that his labor history professors never mentioned the exploited workers on their own campus. “I regret that my friends and I didn’t pay more attention to university labor issues while we were there.”

“Thanks, I’m used to it.” She waves away the university. “So you’re an Internet horticulturist. How does that work?”

Go with the flow, he tells himself, allowing his breath to escape slowly, picturing Miles Davis raising his cool horn to his lips. “People will consult with me about designing their gardens according to the ideas I was telling you about on the porch,” he says. “A lot of urban folks are getting interested in how they relate to Earth.” He makes sure to say Earth so she can hear the capital E. It bothers him that all the other planets get their names properly capitalized while our own is written with a small letter, like she’s just an ordinary thing. He will have to mention that to the kids next time he…Demetrius waves his hand in the air to bring his mind back to the here and now. “People want to raise food, create a more natural environment, better air, more beauty.”

Samantha looks up from her book. “You make farms?”

“Urban farms, I guess. Tiny ones that don’t use a lot of space. I’ll help people with the design and plant selection. Charge an hourly rate, or maybe by the size of the garden. And then for ongoing consultations,” he concludes gamely.

He sees Marlie narrow her eyes. “So this project isn’t running yet?”

“No, but it’s ready to go!” Demetrius gestures toward his bag, as if it’s all in there. To his surprise, he feels a sprig of genuine enthusiasm for this idea he’s just grabbed out of thin air.

“I guess people do pay for stuff way more ridiculous than that,” his host remarks, then makes a comic face. “Sorry! I don’t mean your idea is ridiculous. Problem is, it’s too sensible. People like to spend their money on fast food and junk electronics.”

“If people are given better choices they do better,” Demetrius asserts, folding his arms over his chest to steady himself. He recalls cajoling the crew kids. “We’ll grow radical radishes,” he had assured them as they stood skeptically in front of the patch of land Demetrius had marked off to start their garden last February. “Black Power beans, cop-repellent cabbage. Transformational tomatoes.” The kids had laughed. But they trusted him, so they let him talk them into becoming gardeners.

The garden itself had done much of the convincing. The young people found themselves drawn to the gleaming tools, the tiny seedling pots, the allure of grossing out their siblings with pet earthworms...

Focus, he admonishes himself again, opening his eyes wide. “People can be smart if you give them a chance.”

Marlie nods thoughtfully at her guest. “I guess that’s the premise of this collective: to create an opportunity for us to live in a more intelligent way.”

Ana Violeta’s stern voice speaks up inside Marlie’s head: “Mami, remember you’re trying to pay the bills! Talk to him about the rent!”

“I know, hija, don’t worry,” Marlie responds to her absent daughter.

The stranger’s expression of amiable puzzlement alerts Marlie she's spoken aloud. In confusion, she looks up at the ceiling. It gives her a benevolent nod.

Over the edge of her book, Samantha regards the stranger, afraid he’ll look at her Abue in that frowny way some people do when her Abue speaks to somebody who’s not actually there. But he keeps looking friendly, only a little confused. Mr. Benson Cole or Cole Benson—Samantha can’t remember which—has a nice smile. His teeth aren’t too shiny or too big, but just right.

After a glance over at her grandmother, who is gazing up at the ceiling like she often does, Samantha goes back to studying the new person. He reminds her of a peach, with his fuzzy sweater and roundish tummy, even the bit of fuzz on his chin. Thinking of peaches makes Samantha hungry, which reminds her of an important custom in British books. “Abue, can I serve him tea?”

“Tea would be super!” The words leave Demetrius’s mouth before he can stop them. He envisions Granny Gus’s comfortable form leaning over her wicker porch table, pouring tea into her yellow china cups, and himself reaching for a warm cookie from the batch he’d just removed from the oven. Suddenly, hunger and exhaustion hit him like a punch to the stomach. No longer able to wait for an invitation, he takes a shaky step forward and drops into a chair by the big table. His bag thumps on the floor. He gives Marlie a weak smile. “Sorry, I’m fresh off the bus.” He hardly knows what he’s saying—random words to explain his extreme weariness.

Marlie nods sympathetically, a bit puzzled by his phrase, which she thought meant ‘just arrived in town from the country.’ But hadn’t he said he’d been in town for a while, trying to sell plants? Getting her English precisely right, including accent, idioms and slang, was a fetish of hers. Maybe African Americans use the expression differently? She’ll ask Laranda about it sometime.

In any case, she now sees he’s really tired. She looks out the window. The last rays of sunlight are fading. No time to make the rice dish; she’ll just scrounge what she can. She needs an early bedtime to make up for the sleep she lost last night to the helicopter.

Gratefully, Demetrius watches the woman open the elderly fridge. She digs out a box of sesame crackers, half a head of cauliflower, a wrinkled red pepper, an open can of refried beans, and a wedge of cheddar cheese, laying them in a row on the counter. Finally, she brings out a small paper bag and peeks into it. “Samantha,” she says, pinching the bag as if trying the ripeness of a fruit. “These are blueberry bagels, right? I mean, that is the reason they’re blue?”

The child, who has filled a dented red kettle and carried it to the stove, glances over at the bag. “Abue, we just got them from the Happy Hog day-old bin, remember?”

“Of course, just kidding.” She smiles at Demetrius, who does his best to smile back. He can’t joke about food of any color after twenty-four tough hours without it.

He turns his gaze to the girl, who has hefted the full kettle onto a front burner of the oversized range. She strikes a match, holds it to the gas ring, and turns the knob.

Awful young to be lighting that old stove, he thinks. But then, so was he. Barely nine when he came to live with Granny Gus in the house she inherited from her late husband’s side of the family out on the Maryland Eastern Shore, Demetrius and his grandmother had agreed that he’d do half the housework, including cooking, ironing, and using the push mower with its sharp blades. She required him to do these things safely, and he had.

Marlie brings the cracker box, bagel bag, bean can, and cauliflower to the table and forms them into a circle next to the overflowing tray of plants, placing the cheese and red pepper in the center. She sets a plate, a smooth table knife, and a small fork in front of him, and lays two more places. “Help yourself, Mr. Benson,” she says graciously.

He nods his thanks, thinking he must ask her to call him by his first name—but what is it?