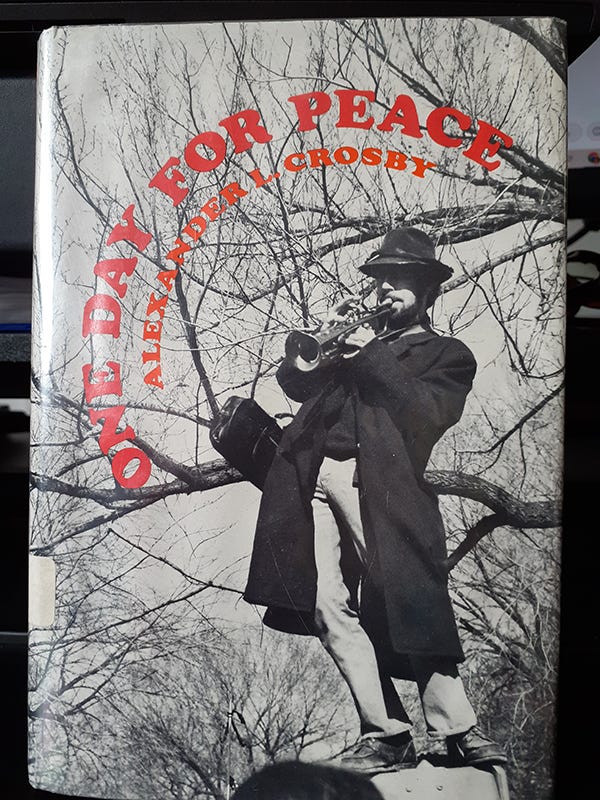

This is a deeper look into the novel featured last week, One Day for Peace, by Alexander R. Crosby. It helped that the book finally came in the mail!

Reading the full story (last week I had only summaries and reviews) convinced me it’s an even more important work than I had first thought. Among the 53 U.S. novels Dr. Deborah Overstreet identified in her study of fiction for young people about the Vietnam War,1 just 30 mentioned the antiwar movement at all, and of these, One Day for Peace is the only one that truly centers the US peace movement in a sympathetic portrayal.

Most of the other novels Overstreet reviewed depict the movement or activist characters in negative, stereotyped, disrespectful, superficial, or inaccurate ways. Or not at all.

One Day for Peace is unique in offering middle grade readers an example of what I term full and fair representation of activists.

In One Day for Peace…

Young Jane Simon learns that Jeff, who used to deliver her family’s milk, and with whom she had developed a warm friendship based on their shared interest in nature, has been killed in Vietnam. In her grief, Jane discusses her friend’s death with her father. They talk about the injustice of the Vietnam war and what she as a young person could do about it. First she decides to ask the US President why the war is happening. The dismissive, dishonest response she receives convinces her that “kids could do it better.” Her parents support her but leave the actual choice of what to do up to her.

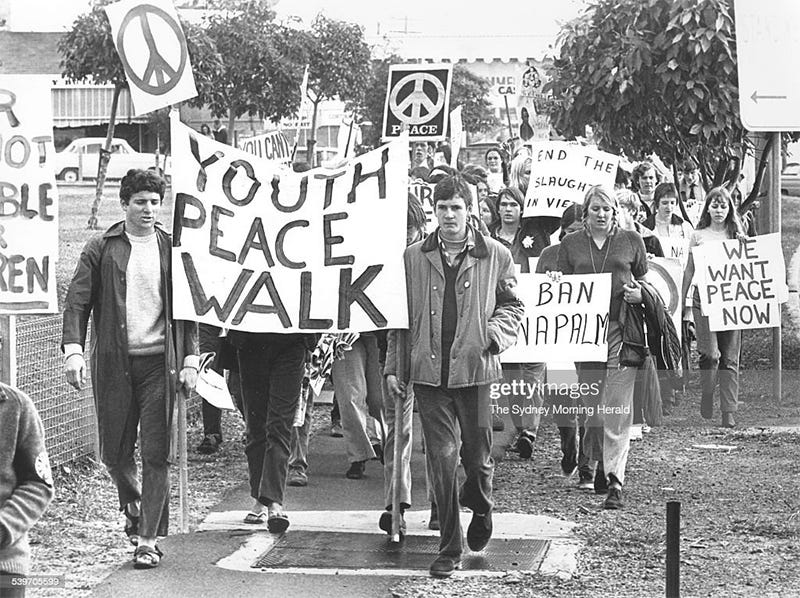

Jane and a few other young people, Black, Puerto Rican, and White, form the Winchester Peace Committee, named for their small town. The committee organizes an antiwar parade to march along the town’s main street, led by the young people and trumpeter-teacher (pictured on the novel’s cover). The youngsters visit town hall, and manage to see the mayor. Other adults join them, some from the start, others once they see that the cause has picked up a lot of support, both because of their organizing and because of local publicity, both sympathetic and critical.

When the day arrives a surprisingly large crowd gathers to march. They pass a peace banner unfurled from a factory roof by some workers—Jane remarks that the wealthy owner won’t be pleased.

With hundreds of townspeople joining in, they are a great crowd by the time they reach the park, where they hold a rally and plant a tree.

What Makes One Day for Peace so Commendable?

- Unlike much of the fiction featuring activists that does exist, One Day for Peace shows actual organizing work. We see the young people meeting together, door-knocking, talking with journalists, painting placards, facing down considerable opposition—including threats from the principal, nasty letters to the newspaper, and physical bullying.

Perhaps the mayor’s warm reception of Jane and her friends is unlikely. But the author paints a realistic picture of the young people in the committee brainstorming, joking and arguing, just like real activists.

Often activist appearances in fiction lack knowledgeable, sympathetic depiction of everyday activities they engage in, so this story’s invitation to enter fully into the activist characters’ world is compelling and refreshing.

- Adults and young people are part of the movement. This story focuses on a family, like many in the U.S.—including my own—where everyone came together in opposing the Vietnam War. In this story Jane is heartily supported by her parents, as well as a number of teachers and other adults.

Overstreet’s study finds that, other than in One Day for Peace, a preponderance of antiwar characters in the other books are young people whose parents and other relatives are rabidly against them, calling them cowards and traitors. While divided families certainly were common, they were not necessarily the norm, and it remains the author’s choice to highlight negative or positive attitudes toward the peace movement, knowing that young people are likely to rely on what they read because they have few other points of reference.

- The protagonists of One Day for Peace are multiracial. One young Black character, Fred, mentions the oft-cited paradox that Blacks and other people of the global majority were being sent to the other side of the world ostensibly to fight for democracy, while being oppressed at home. The story also indicates that, contrary to stereotypes, even though Whites were the majority, the antiwar movement was not made up exclusively of privileged White students.

- One of the young peace committee members, Donald, whose parent is a lawyer, tells the others about the FBI’s use of agents provocateurs to infiltrate and destroy peace organizations by implicating them in crimes. He’s responding to another boy, Roberto, who jokingly suggests throwing a bomb at a bank. In addition to adroitly introducing information into the dialog, this exchange, which leads Roberto to quickly withdraw his proposal, proactively refutes the all-too-common stereotype of activists as bomb-throwers. In fact, during the parade a cherry bomb is thrown—by a pro-war person on the sideline.

What does this mean for today?

Dr. Overstreet points out that in Lies My Teacher Told Me, James W. Loewen’s scathing analysis of major high school history textbooks, the author finds that…

… not only was the [Vietnam] war given short shrift and the antiwar movement practically unmentioned, but … both were presented inaccurately.”2

Given this glaring hole in US young people’s education, Dr. Overstreet suggests historical fiction may be an indispensable alternative for introducing them to this period where youth played such a crucial role. Distorted portrayals deprive young people of access to how a previous generation actively and successfully confronted this major conflict, and of their chance to vicariously experience the peace movement, which well-crafted fiction can provide.

Novels like One Day for Peace present a rare picture of what a small corner of the immense antiwar movement might have looked like. But we need many more such portrayals so that young people find information, understanding and examples that can inspire them to organize their own responses to the endless wars this country continues to wage around the globe.

“One, Two, Three, Four! We Don’t Want Your F**king War! The Vietnam Antiwar Movement in Young Adult Fiction,” by Dr. Deborah Wilson Overstreet, Associate Professor of Language Arts Education, University of Maine at Farmington. The Journal of Research on Libraries and Young Adults, Volume 10 N. 1, March 2019.

Ibid., p. 2.